The Language of Better Health

LESS TALK, MORE REALITY: APPLYING TYRANNY OF WORDS TO FP

Reading time: 20 mins

Introduction

At some stage during sessions at our facility, your FP practitioner may suggest reading the “Tyranny of Words” (ToW) by Stuart Chase, as part of FP protocols. The ToW explores the impact of semantics (the study of meaning of words) on our thoughts and behaviours. ToW emphasises that words aren’t just a communication tool; they’re a powerful stimulus for our nervous system that can trigger physical and emotional responses, with downstream consequences on our behaviours and movement quality.

FP protocols suggest learning and applying some of the concepts introduced by ToW. The goal of this article is to educate our clients on some of the conceptual frameworks and applying these to help understand FP’s approach to training. If you found this article useful, we recommend looking into the list of resources at the end of this article.

Binary Thinking — Is this All Wrong or All Right?

Binary thinking is placing things into absolute opposites. For example, right/wrong, good/bad, true/false, 1/0. While these categories do exist, reality is more nuanced and complex. Binary thinking tends to happen when we ignore the situation or context. Identifying binary thinking and unraveling it using context is important when the key issue is rigid thinking.

Reality is rarely “all wrong” or “all right”

Case I: A particular exercise is entirely “good” or entirely “bad”.

Every exercise, if done “correctly” has certain benefits and certain unintended harmful side effects (negative externalities) like pain and imbalances. FP exercises have more benefits and less negative externalities compared to conventional exercises. These come from applying concepts contained in the “first four” functions (stand, walk, run, throw) to our training.

For example, let’s compare a barbell deadlift to a RG bar lift exercise. For the barbell deadlift, the backline muscles are highly engaged at the bottom, but some of these disengage towards the top of the lift. This causes compression on the spine that’s unavoidable especially when progressing to higher weights. The RG bar lift disperses tension evenly across the entire body and maintains this during the entire lift. The spine is much less likely to get compressed versus the deadlift and we recruit more muscle groups to help the lift. In terms of bang-for-buck, the RG bar lift has far more benefits and less negative externalities than the barbell deadlift.

This gets more nuanced depending on whether the exercise was executed “correctly”, and the principle of maladaptation, meaning repeating the exact same exercise over time reinforces imbalances. FP practitioners observe how the client responds to a corrective exercise and make a judgement whether it’s “better” or “worse” for them in that context.

The top phase of the barbell deadlift compresses regions like the lower back. The RG bar backline lift, demoed by FP founder Naudi Agular has more evenly dispersed tensions.

Case II: Performing a movement pattern and not getting it “perfect”

Anytime we perform a movement pattern, it's never going to be “perfect”. Everyone, including professional athletes, have structural imbalances that prevent “perfect” movement. For example, Usain Bolt has a scoliosis that affects his sprinting mechanics. Many of these imbalances are highly ingrained and can’t be addressed in a single FP session. It’s more useful to frame movement in terms of aiming for “perfection”, but acknowledging we can only get “better”. This is also influenced by factors like our current energy levels, mood, and the weather/season.

It’s important to mention when the practitioner says “good” or “bad” during a session, they’re using these words as behavioural tools (positive and negative reinforcement). Here “good” means “continue that pattern” and “bad” means “stop doing that pattern”

Usain Bolt’s scoliosis prevents “perfect” symmetrical gait mechanics.

Case III: Certain foods, like sugar are “bad” and should be avoided

In The Truth About Sugar and Your Metabolism, FP practitioner Mike Mucciolo discusses how sugar can be useful depending on the client’s metabolism, hormones, energy needs, and individual context. For example, the body uses glucose from carbohydrates like sugar efficiently. In certain contexts that place high demand on the brain e.g. during a FP session, consuming some natural sugar like a piece of fruit a couple of hours before could be useful. In other contexts, such as the client is sedentary and chronically inflamed, consuming excessive processed sugar like sweets or candy might fuel inflammation. The FP anti-inflammation diet e-book (pages 23-24) covers the contextual effects of sugar.

Sugar is neither “bad” nor “good” – it can be beneficial or damaging depending on the context.

Levels of Abstraction

Abstractions are simplifications of things in reality. They’re useful because they let us communicate ideas efficiently. For example, a map is a simplification for the actual place (territory). It shows important landmarks like buildings and roads, but leaves out less relevant details like trees and potholes.

A map is an abstraction of the territory.

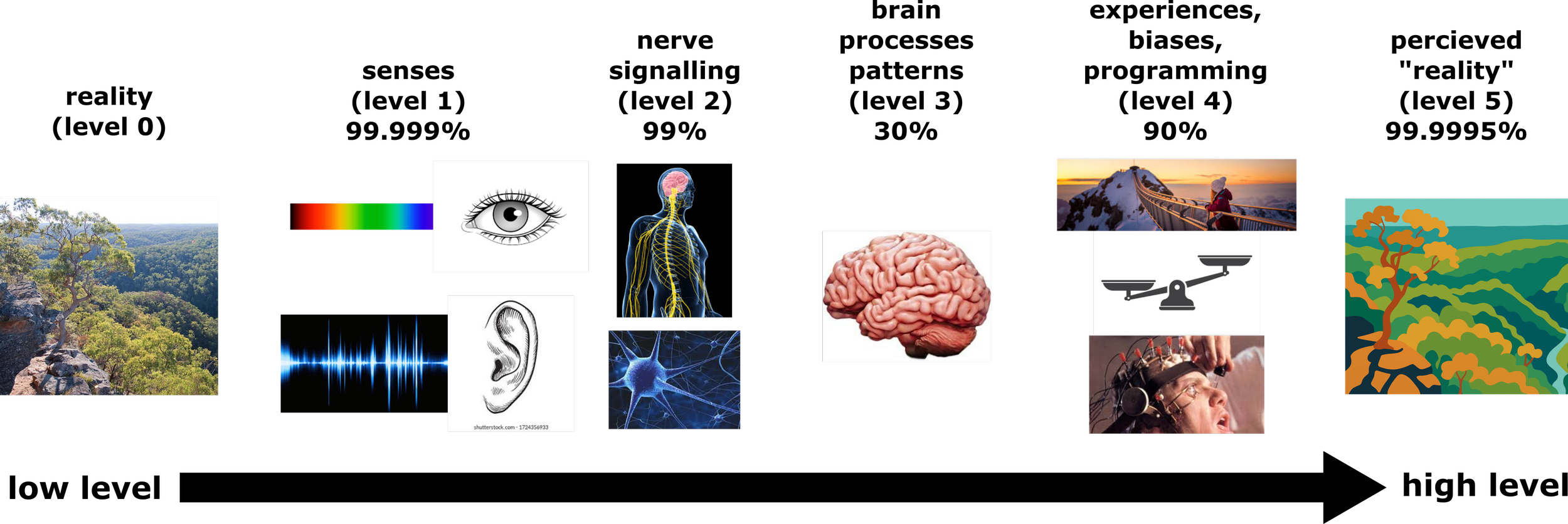

It’s important to understand that our perception is also an abstraction. There are 5 levels of abstraction from reality to perception:

Level 0: Reality itself. It includes the light waves, sound waves, and atoms/molecules that make up reality.

Level 1: Our senses (e.g. sight, sound, smell, interoception, proprioception) detect a slice of reality and convert this information into signals.

Level 2: Our nervous system converts these signals into electrical/chemical “code” our brain can process.

Level 3: Our brains process this “code” into patterns like motion and texture.

Level 4: Our brain overlays these patterns with our experiences, biases, and programming.

Level 5: Our perceived “reality” summarises level 4.

Going from reality to our perception, we perceive a fraction of reality – only 1 in 10 million of the original details remain. Knowing this helps us understand that our perceptions are at best very limited, we can’t always trust our senses, and we’re highly subject to our biases and programming.

Levels of abstraction from “reality” to our perception. Percentages are the details altered in each level.

Humans are unique because we use language to abstract even further than level 5. This allows us to communicate complex ideas but it can also lead to misunderstandings:

Level 6: Attaching words to perception e.g. “plank”, “deadlift”, “squat”, “sprinting”

Level 7: Categories and generalisations e.g. “cardio”, “strength training”, “functional training”, “healthy eating”, “superfoods”.

Level 8+: Ideologies and symbolic constructs, often specific to cultures e.g. “strength”, “aesthetics“, “fitness industry”, “health is wealth”, “no pain, no gain”.

Levels of abstraction are most useful when the key issue is precision vs generalisation.

Case I: FP and the Fitness Industry

Most of the fitness industry is stuck at higher levels abstractions (6+) that are too general or poorly tied to reality:

Level 6: Basic labels like “strong”, “weak”, “deadlift”, “back squat”.

Level 7: Generalisations like “general strength”, “athleticism”, “mobility”.

Level 8+: Catchphrases like “no pain, no gain”, tribal identities like “powerlifters”, “yogis”, “bodybuilders”, and cultural narratives like “yoga is spiritual”, “fitness for aesthetics”

The reality (level 0) is how humans stand, walk, run and throw. FP takes a first principles approach asking “What’s the base reality of human biomechanics?”:

Level 6: FP looks at whether a particular exercise e.g. “deadlifts” (level 6) actually helps optimize the “first four” functions.

Level 7: Instead of building “general strength”, FP aims to build strength in different contexts that relate back to the “first four” functions. For example, someone can be “strong” during a deadlift but poor at lifting actual bulky objects because the mechanics (context) of deadlifts doesn’t mimic lifting actual objects.

Level 8+: Rather than applying catchphrases like “no pain, no gain” (level 8+) FP determines why the client feels pain and targets the root cause in terms of the imbalances happening in the “first four”.

FP does use higher level abstractions e.g. labels like “step press”, categories like “dynamic exercise” and slogans like “Train Habitually, not Intentionally". The difference is FP’s abstractions are more tied to reality because they’re constantly tested against the clients' biomechanics.

Most of the fitness industry is stuck at the higher level abstractions that don’t tie back to reality.

4. The Semantic Triangle — Word aren’t Reality

Language (words) is a symbolic map, not the territory (reality). The semantic triangle is a diagram that breaks meaning into three parts:

The symbol – How we refer to the thing, often a word.

The concept – What we think of when we hear or see the symbol.

The referent – The real-world thing.

The dashed line shows how symbols don’t directly connect to the referent in reality – they pass through our mind as mental concepts that are shaped by our experiences, biases and programming. Meaning and reality match up when these three parts are consistent with each other. The semantic triangle is most useful when the key issue is the meaning of words.

Case I: “Healthy Eating” in Diet

Symbol/word: “Healthy eating”. On its own, these are just words with no link to reality.

Concept: What we think of when they hear the words. This could include “more veggies, less meat”, “high protein, low carbohydrates”, “more carbs, less oil”. The concept doesn’t have a uniform meaning for different people.

Referent: The actual food we put on our plate.

Possible Misunderstandings: The word “healthy” can have multiple meanings depending on the context. For example, “healthy” meaning appropriate for a person’s medical condition versus “healthy” meaning what makes a person feel good.

The concept of “healthy eating” is vague. For example, in the context of a personal goal it might mean a calorie deficit, whereas a cultural view of healthy eating could be fresh, seasonal foods.

The referent can be different depending on how we define what’s considered “healthy”. For example, if we compare “healthy eating” from a vegetarian versus carnivore dieter’s perspective.

How FP clarifies “Healthy eating”: FP frames the concept of health in terms of optimizing the processes of mechanotransduction (MTD), biochemistry, and bioenergetics that occur in our cells. “Healthy eating” for FP means foods that optimise these processes, especially MTD or how our cells convert movement into chemical/electrical signals that support growth, repair, and function. In FP, we use biomechanics to enhance MTD. Inflammation – the body's injury healing mechanism – prevents good biomechanics by causing pain and stiffness when chronic. Therefore, “healthy eating” in the context of FP means foods that promote anti-inflammation.

The referents include the FP anti-inflammation diet e-book, which explains which food groups to prioritise/avoid for anti-inflammation, and the FP before-after results showing the improvements to diet-related inflammation and biomechanics (less bloating).

Case II: “Functional training” in Fitness

Symbol/word: “Functional training”.

Concept: What people think of when they hear the words. This could include “deadlifts and backsquats”, "bodyweight exercises", “yoga”, ”Crossfit”, and “HIIT exercises”, all concepts that don’t have uniform meaning.

Referent: How we actually train in the gym/home.

Possible Misunderstandings: The word “functional” has multiple meanings depending on the context. For example, in physiology, it might mean the body working well as a system with no pain. Culturally, it might mean how well it ties to traditions or social norms.

The concept of “functional fitness” is vague and could be influenced by personal goals, education, marketing, and culture. For example, it might mean supporting a person’s personal fitness goals like weight loss. From a marketing context, it might mean what’s “trendy” or “popular” at that time.

The referent can be different depending on how we define healthy. For example, if we compare “functional training” for a yogi versus a F45 athlete versus a calisthenics athlete.

How FP clarifies “Functional training”: FP frames the concept “functional” in terms of optimising the functions humans adapted to do the most – standing, walking, running, and throwing. Therefore, functional training for FP means training that respects these “first four” functions. Related concepts we teach our clients include fascia, myofascial slings, tensegrity, elastic recoil, structural integrity, and avoiding dysfunctional behaviours.

The referents include the training protocols (corrective and dynamic exercises based on the mechanics of the “first four”), equipment/accessories (myofascial tools, FP equipment), and the posture/gait results.

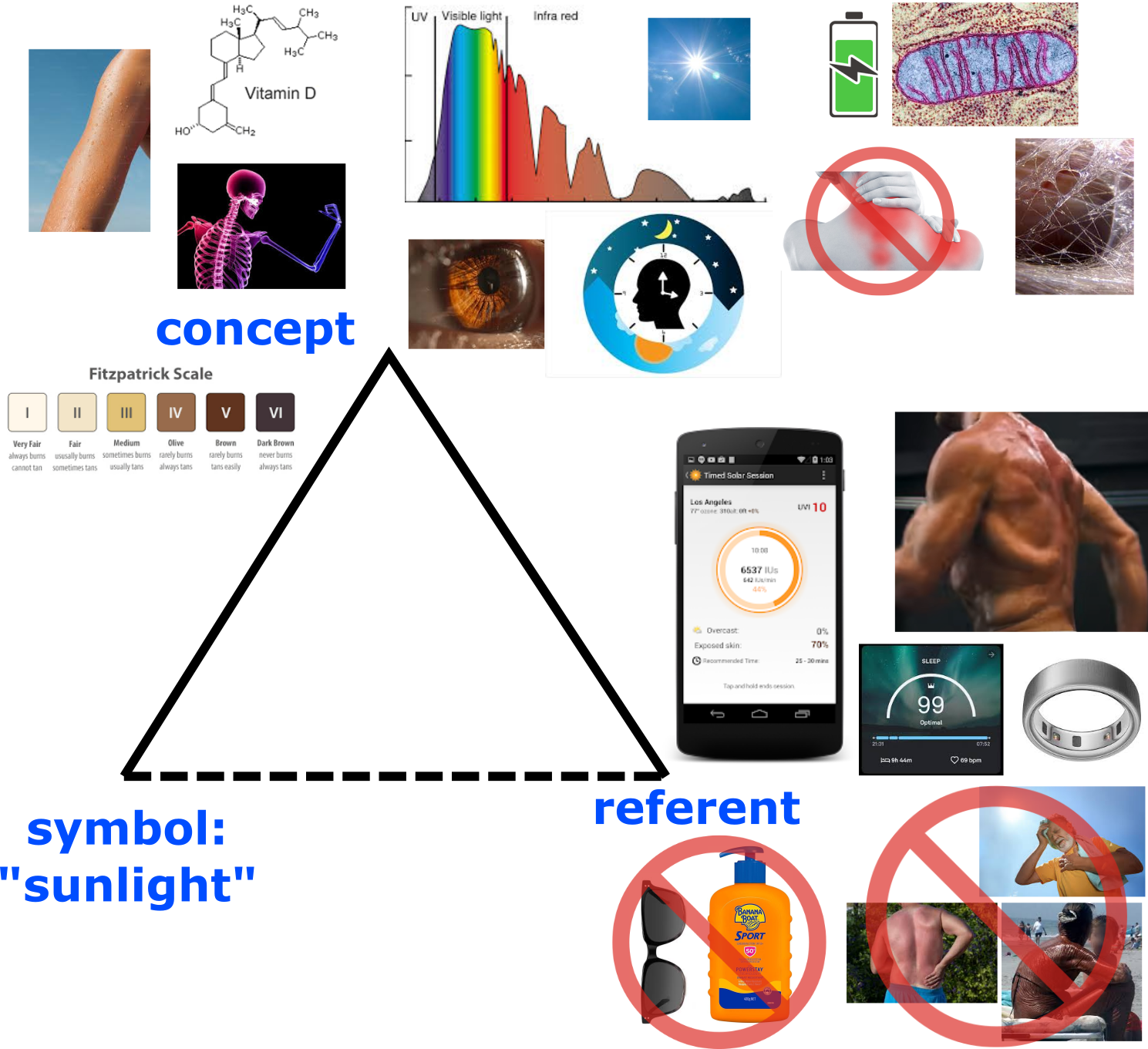

Case III: “Sunlight” in Health

Symbol/word: “Sunlight”.

Concept: What people think of when they hear the words. For example, “brightness”, “vitamin D, bone health”, “happiness/optimism”. Depending on your culture you might associate sunlight with “poorer people doing farmwork” or “wealthy people on holiday”. Depending on your personal experiences with sunlight, you might associate more positively e.g. “playing sports outside with friends during summer”, or negatively e.g. “I got sunburnt last time I went outside during summer”.

Referent: The actual Sun that emits different types of light waves including infrared (IR), visible and ultraviolet (UV) that interact with the body (skin, eyes, hormones).

Possible Misunderstandings: The concepts associated with “sunlight” are heavily influenced by binary thinking. In Australia, we have a culture of enjoying outdoor life and avoiding the sun due to high skin cancer rates.

Certain types of light waves have effects that can’t be sensed with our eyes so they feel more abstract. For example, we only perceive the effects of IR light on our body as heat and fascial hydration. We perceive the skin tanning and immune effects of UV light hours to weeks after exposure.

Our associations with sunlight can be very polarised depending on our personal experience.

How FP clarifies “Sunlight”: FP frames the concept of “sunlight” in terms of bioenergetics or how our cells use energy from nature to enhance our health. Sunlight is neither “bad” nor “good” – it’s a tool we can use to optimize health, but it can have negative effects when misused.

The amount and types of light waves from sunlight vary with the location, weather, time of day and the season. For example, in Sydney during summer:

IR: Present from sunrise to sunset. Helps with energy production, anti-inflammation, and fascial health.

Visible: Present from sunrise to sunset. Helps regulate circadian rhythm and sleep.

UVA/UVB: 2-3 hours around solar noon. Helps with mood, blood pressure, bone strength, and immune health (vitamin D).

FP protocols suggest that all clients need sunlight and the dosage depends on the individual. For example, someone with Fitzpatrick type 4 skin tone might absorb 3 hours of Summer sunlight without burning, while someone with Fitzpatrick type 1 skin tone sunburns after 30 mins. To absorb adequate midday sunlight without sunburn, clients may need to first develop a “solar callus” by exposing their skin to the IR light during the morning/afternoon. FP observes clients with better biomechanics tend to be able to absorb more UV light without burning, and adapt well to sunlight. Often, when clients have adverse reactions to sunlight, this solar callus wasn’t developed and their skin was suddenly exposed to a high UV dose e.g. the beach during the midday Summer.

Referents include the Dminder app to track optimal UVB absorption for vitamin D without sunburn, tracking readiness/sleep scores using devices like the Oura ring, and avoiding substances that block sunlight including sunglasses/most sunscreens, and going under the shade when the sunlight is too intense. Tissues with optimal amounts of sunlight are tanned, look plump/hydrated/glowing and behave viscoelastically during dynamic movements like sprinting. Tissues that get too much sunlight and poor biomechanics look dehydrated/wrinkled/burnt, and don’t respond well to corrective exercises.

Conclusion

We introduced three conceptual frameworks from ToW that we can use to analyse whether our language is consistent with reality. Binary thinking is most useful when the key issue is rigid thinking blocking perception/causing conflict. Levels of Abstraction are most useful when the key issue is generalisation vs precise language. The Semantic Triangle is most useful when the key issue is the meaning of words. We applied each of these to different situations relevant to FP training to clarify common concerns and issues clients have.

Resources

FP founder Naudi Aguilar’s lives on IG

ToW by Stuart Chase

Science and Sanity by Alfred Korzybski (the OG in semantics)

Futurist Jacque Fresco and issues with communication: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3